Timeline

By 1967, opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War had been growing on college campuses across the country for several years, including at UW–Madison, where a 1965 “Teach-In” by 29 faculty members about the Vietnam conflict drew an estimated 1,500 students. In late February of 1967, UW–Madison students blocked offices in Bascom Hall to protest the recruitment efforts on campus of the Dow Chemical Company, which made napalm, a flammable gel that horribly burned its victims. Students organized another round of protests against Dow and the war on campus Oct. 17–18, 1967, as a precursor to a large national antiwar march the following weekend in Washington, D.C. The events of Oct. 17 played out peacefully — about 125 demonstrators picketed on the terrace of the Commerce Building, and 15 to 20 people protested quietly inside. The next day, however, became “the country’s first university protest to turn violent,” according to Madison historian Stu Levitan. Here is how the day unfolded:

8:30 a.m.: Recruiters from the Dow Chemical Company arrive at the Commerce Building (now Ingraham Hall, 1155 Observatory Drive) to interview students for prospective jobs.

10 a.m.: About 200 to 250 protesters begin gathering at the foot of Bascom Hill.

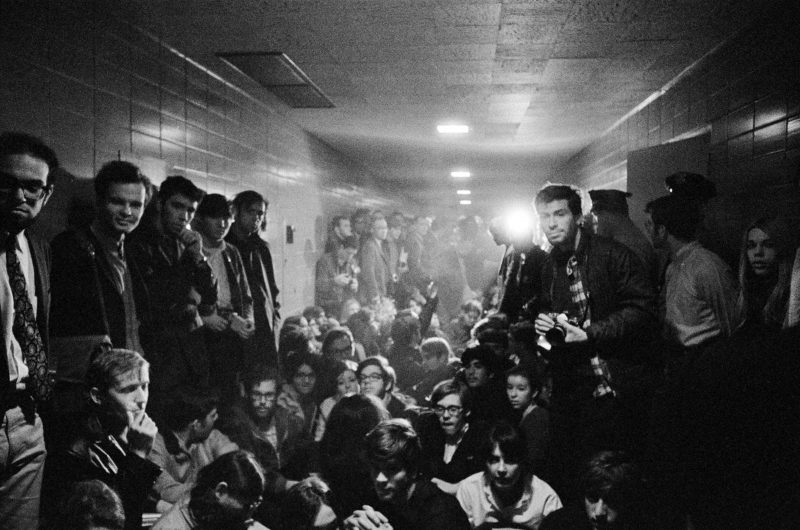

10:30 a.m.: Dozens of student demonstrators enter the Commerce Building and surround the four police officers stationed outside the room where the Dow interviews are being held. The students sit down, blocking the entrances to many rooms.

11 a.m.: About 200 people are now completely filling the east-west corridor, yelling, singing and chanting.

11:15 a.m.: A student wanting to interview with Dow is refused entry by demonstrators. One protester puts his arm around the neck of the prospective interviewee and holds him. University Police Chief Ralph Hanson tells three protesters blocking a door that their action constitutes disorderly conduct and that they are under arrest. As police officers try to arrest one of the three, other students grab onto him so that he can’t be dragged away. With the crowd becoming more hostile, Hanson halts the arrest.

11:30 a.m.: An additional 150 to 200 students are now filling the north-south corridor, many of them spectators. Believing the situation beyond his control, Hanson calls Madison Police Chief Wilbur Emery and tells him to send every available officer to campus.

12 p.m.: City police officers, equipped with helmets and riot sticks, begin to arrive. Emery tells his police officers not to swing their riot sticks and to use them only to fend off blows.

1 p.m.: Hanson enters Commerce and declares two or three times through a bullhorn that the assembly is unlawful. He tells protesters they must disperse or they will be arrested. He is jeered and cursed. No one leaves. An assistant to the university president is struck in the face by a protester.

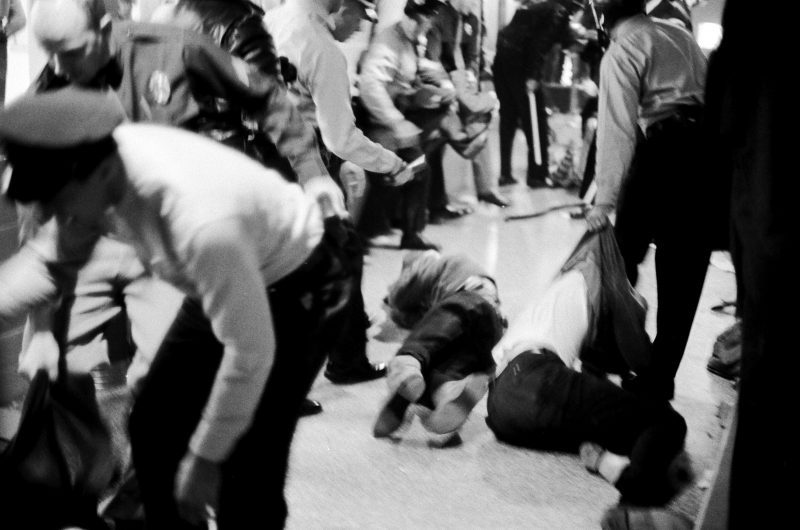

1:30 p.m.: Attempts to negotiate with protesters fail. The crowd outside Commerce begins to grow by the hundreds. Hanson re-enters Commerce with police officers. Some witnesses later say the crowd surged forward to force the police back out the door, while others say they did not feel or witness a surge. Police officers, heavily outnumbered and facing an increasingly agitated crowd, begin striking protesters with riot sticks and dragging them out of the building. Some observers later say police used their riot sticks with too much force, while others say the police showed restraint while being pulled, pushed and grabbed at by demonstrators. Emery later tells the state Legislature that his men were “fighting for their lives.”

1:45 p.m.: With the corridors cleared, the melee moves outside, where demonstrators begin throwing rocks, sticks, pipes, shoes and bricks at police and at the Commerce Building. Police strike back at the crowd, sometimes using riot sticks.

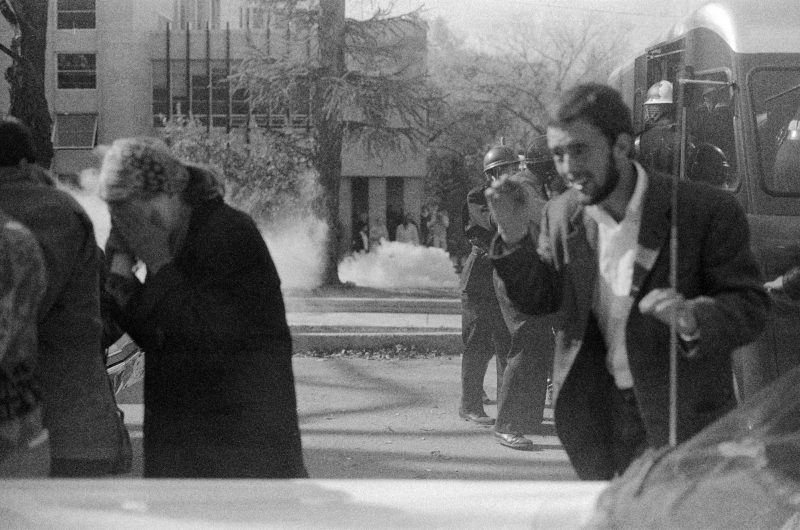

2 p.m.: Emery decides the crowd must be broken up and orders the use of tear gas. It is the first time tear gas is used on the UW–Madison campus. Emery calls the Dane County Sheriff’s Office for officer reinforcements. By this time, at least three officers have been seriously injured and dozens of protesters have sought medical attention.

3 p.m.: About 150 officers establish a perimeter around the Commerce Building to gain control of the crowd. The show of force serves to reduce further incidents and the crowd slowly disperses.

5:30 p.m.: All protesters have departed and the police have left the campus.

9 p.m.: More than 3,000 students amass on Library Mall and vote to boycott classes until the administration permanently bars city police from campus and agrees not to punish leaders of the Dow sit-in.

Aftermath: The protest made national news, propelling UW–Madison to the forefront of the anti-war movement. Many students, horrified at what they considered police overreaction and brutality, became radicalized and turned strongly against the police and the administration. By 8:30 a.m. the next morning, nearly 2,000 students had gathered for a rally near the Abraham Lincoln statue outside Bascom Hall. Meanwhile, the Dow protest infuriated conservatives, police allies and war supporters. The State Assembly passed a resolution calling the demonstration “a flagrant abuse and perversion of the treasured traditions of academic freedom.”

For years to come, the campus would be roiled by antiwar demonstrations, some involving tear gas and the National Guard. On Aug. 24, 1970, the violence turned deadly. Four protesters bombed Sterling Hall, home of the Army Mathematics Research Center, killing postdoctoral fellow Robert Fassnacht.

In the years following the Dow demonstration, the Madison Police Department dramatically changed its policies related to large protests. A team of officers specially trained in crowd management now leads the response, with the goal of keeping officers in “soft gear” and avoiding riot gear. The emphasis is on working proactively with protesters to facilitate a safe demonstration. The department trains frequently with the UW Police Department and has developed a mounted horse patrol that helps peacefully manage large crowds.